Introduction

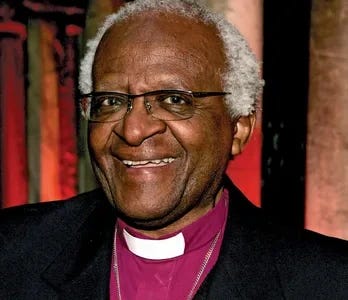

In March 2004, shortly after finishing graduate program, a dear friend who was originally from Zimbabwe, Dr. Eliakim Sibanda informed me that Archbishop Desmond Tutu would be speaking at the University of Colorado in Boulder. I and “Kim” as we used to call him were like Siamese twins at the Joint Program at the University of Denver. He started the program before me and when I was admitted, he would recommend which political theory or sociology courses to take especially with Professors Alan Gilbert and Paul Colomy who were regarded on campus as “walking encyclopedia.” On weekends, we would chill over pizza and Zimbabwean cuisines as we watched boxing interspersed with discussions on current and past political events nationally and globally. “Mr. President” - he would often refer to me with strong conviction that I am somehow destined to be president in the Motherland in the future. I would comically respond: “thank you, my Honorable Senator from Bulawayo.” He came from the Bulawayo area of Zimbabwe. We would discuss on-going struggles especially in our dear continent as these issues relate to the rest of the world whether it was the policy effects of International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, (WB),Structural Adjustment Policies (SAP), or other non-Governmental organizational policies on Africa. As members of African Students Union at college campuses in both Denver and Boulder, the vibrant nature of the discussions was as momorable as it was profound. I regularly visited the University of Colorado Boulder campus and was an avid user of their Norlin library just like the ones in Denver. Boulder was like a second academic home to me. Therefore, going to hear Arbishop Desmond Tutu was an icing on the cake for the evening. I had read his books and sermons but never met him in person, so this was a unique opportunity to do so. Those were the good old days.

Why Archbishop Desmond Tutu?

The first part of this week was graced with mixed emotions. On one hand, was what some called avalanche of blessings I received from Africa that gladdens the heart and makes the face radiant with hope, optimism, and gladness. On the other hand was not a few messages I heard about friends and few people I know struggling with personal issues, traumas, and sufferings of immense proportion such that on hearing them, I was deeply moved into tears. It was then that I began to reminisce over the early prayers of pilgrims such that I had to look into their deeper significance and meaning for the present moment. Among them was this particular prayer:

“Almighty God: We make our earnest prayer that Thou wilt keep the United States in Thy holy protection; that thou wilt incline the hearts of the citizens to cultivate a spirit of subordination and obedience to government, and entertain a brotherly affection and love for one another and for their fellow-citizens”

Certainly, one may critique the limitations of the aforementioned prayers because of the nature of social and political discourse at the time, but the spirit and intent of the last few words, I believe, will find resonance with Archbishop Desmond Tutu. This is more so with the emphasis on the words “brotherly affection and love for one another and their fellow-citizens.” As I was deep in thought on my mixed emotions, my eyes glanced through my booksheves at home and there was the book authored by the Archbishop and also autographed by him when I met him in person at the University of Colorado in Boulder.1 Before his inimitable signature, he even inscribed “God bless. March 2004.” It was so memorable I shook hands after the lecture that it felt like I had visited the third heavens. Even though I had read the book before, this week, I browsed through the content’s page again and thought it is the book for the moment and I would use aspects of it for my current blog.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

The Unviversity of Colorado Hall where Archbishop Desmond Tutu spoke was full and overflowing, and there were loud speakers booming for those in adjoining hallways longing to hear and see him. He needed no extensive introduction: a Nobel Laureate who has long been globally admired for the heroism, courage and grace he demonstrated during the struggle for liberation from apartheid in South Africa. We listened to him attentively, which to me was reminiscent of when we were little kids watching and nodding approvingly at every word spoken by African elders. As the saying goes: “the words of our elders are words of wisdom.” I was also impresed by the ways many young people in and outside the university yearned to hear him, even those from different religious and cultural traditions. He was relatable. He drew upon personal and historical examples, doing so with humor and grandfatherly demeanor that encourages you to want to hear more. As one of the key members of Truth and Reconciliation Committee set up to address past injustices in the country with the goal of healing and moving forward, he carried with him formidable experience that is matched by a few of his contemporaries then and even now. Tutu has a pulpit that speaks to all and sundry of all religous and spiritual background, different political persuasion across races, ethnicities, tribes, and tongues. His was a challenge to the individual and the community, and the world to “see with the eye of the heart.” The incessant challenge on the need to work assiduously toward cultivating love, humility, forgiveness and courage still reverberate with me even after many years of departure from this world. The Archbishop still speaks.

Seeing With the Eyes of the Heart

I reread the chapter on “Seeing with the eyes of the heart” again, and this is the core of the blog for this week. The Archbishop began thusly: “I am sorry to say that suffering is not optional. It seems to be part and parcel of the human condition, but suffering can either embitter or enoble. Our suffering can become a spirituality of transformation when we understand that we have a role in God’s transfiguration of the world…. we must learn to see with the eyes of the heart and not just the eyes of the head.” I must confess that at the time I first read the book, I was struggling with the issue of theodicy - a theological and philosophical concept that seeks to justify the existence of a benevolent and omnipotent God in the presence of evil in the world. At the time, my father’s death at fifty-eight years old in a ghastly motor accident was still fresh in my mind as well as losing a series of family members including my junior sister. The pain of other personal sufferings at the time left me stunned and withdrawn. Like Du Bois after the loss of his first son, I resorted to killing the pain with books. It was the last resort but it did not vanquish the pain. Again, it reminded me of what my father would say when he was alive: “man shall not live by books alone” reversing and transposing the words of Jesus: “man shall not live by bread alone.” He was basically reminding me I was too bookish and that it is good to have other important focuses as well. Desmond Tutu spoke afresh by reminding me that in the universe we inhabit there will always be suffering. God has a dream is the title of the book, which echoes the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. “I have a Dream Speech.” In essence, Tutu is enjoining us that God not only has a dream but also calling humans to be enlisted in making that dream come true. But the journey of life will still be painful in the same way as childbirth is painful, same way there is torment in illness, and anguish in death: “Sadness, longing, and heartache would not disappear.”

The challenge, according to the Archbishop is to see suffering and our role in decreasing it - differently, to see a larger purpose of our suffering, transformed and transmuted to become redemptive suffering. When we let suffering enoble us instead of embittering us, it gives room for us to grow emotionally, spiritually, and morally. The example of Nelson Mandela struck a cord as most people still see him as a good person, a statesman, who embodied forgiveness, love, and humility. He spent twenty-seven years in prison at Robben Island with eighteen of them spent in breaking rocks into little rocks (page 72). He pointed out that Mandela’s eyes got damaged in the process that it was still painful to the extent that photographers would be asked not to use flash when taking his pictures. Mandela went to prison an angry man, but came out after twenty seven years a changed man. According to Tutu: “Mandela mellowed in jail. He began to discover depth of resilience and spiritual attributes that he would not have known he had.” Therefore, he was able to understand the foibles and weaknesses of others and to be gentle and compassionate toward others even in their awfulness (73). In essence, the jail became an instrument of good that was meant to be evil. Suffering transformed and enobled him rather than embitter and destroy his soul. Tutu opined that Mandela would not have become the moral and political leader he was had it not been for the suffering he exprienced on Robben Island. Anger was replaced with forgiveness that he even invited his former jailer to be a VIP guest at his inauguration. That was statemanship par excellence.

Conclusion

We all have experienced different levels of sufferings whether personally or from people close to us. While some may not spend twenty seven years in prison like Mandela, yet we cannot minimise the level of sufferings that befall each individual. A few times that I have been chanced to speak to those in jails through Inside Out programs that teach college level courses in jail brought this home. I came across inmates who have immersed themselves in reading college levels courses that simply stunned me. I told the people in the program that this is definitely one of the unintended consequences of the Prison Industrial Complex. I saw not a few inmates reading college and graduate level books that I was simply impressed by their remarkable achievement. Furthermore, their moral and ethical compass appeared to have been remarkably transformed through the experience. Reading and hearing Archbishop Desmond Tutu has been like a balm over the last few days. It has made me to look at suffering in a different and renewed light, and hopefully will be instrumental in responding to people I indicated in my earlier paragraphs and beyond. Finally, I also take comfort in the words of him who said: “In this world you have tribulations and trials, but be of good cheer because I have overcome the world.” The struggle continues.

Tutu, D. 2004. God Has a Dream: A Vision of Hope for Our Time. Doubleday Random House: New York.

Thank you for sharing the inspirational story and legacy of Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Also remember attending his speech at University of Colorado at Boulder. Great quotes from him; powerful quote about how struggle can either embitter or enoble us. Wish I had visited Robben Island when I was in Cape Town to see where Nelson Mandela was imprisoned but hope to if/when I make another visit.